Venture Capital and the Secretary Problem

If your product is too unique, VCs might simply treat that as "part of the 37%" (or training set), to firm up their hypotheses rather than evaluate for investment

One of the things that people say about some companies that failed to take of is that “it was an idea ahead of its time”. In a lot of these cases, the company would have folded because it failed to raise sufficient capital (companies that raise too much capital are rarely “ahead of their time”).

Why is it that companies that are possibly ahead of their time fail to raise money from venture capital firms? The answer lies in the Secretary Problem.

Now, this is a hypothesis based on my limited interactions with VCs earlier this year when we were trying to raise a pre-seed round. Early on during those interactions, I had written about Elaine’s Sponges. And as we went through the process of talking to VC firms, this hypothesis on “availability of sponges” only got strengthened. So I do have some track record in making such judgments.

One of the observations I had during my interactions with VCs earlier this year is that VCs learn by pattern-matching based on pitches that they receive.

One of the key points of our pitch about Babbage Insight is that “we are not a copilot”. And it is not funny how many VC conversations started going flat after we had uttered this line, which we consider to be a key differentiating factor.

With the benefit of hindsight, one impact that our differentiating factor possibly had is that it messed with the prior in the VCs’ minds. My hypothesis is that VCs develop theses on sectors and ideas by pattern-matching. As they see a number of pitches that have a common thread, they start developing intelligence and domain knowledge around this thread. This means that the next pitch they see that fits into this thread, they can evaluate easily. It is like they already have a pre-trained model that they can fine tune with the new pitch, and thus evaluate it easily.

The problem with going with an idea that stands out too much is that there is no “pre-trained model” that the VC can rely on, and this means they need to invest more energy into the evaluation process. This means you need to put that much more effort to impress them sufficiently that they are even willing to put in the effort to evaluate.

The secretary problem

Now the thing with ideas ahead of their time is that they are actually not THAT unique - there are companies that come later on that manage to do very well with the idea. The problem with ideas ahead of their time is that at the time they come about, VC funds either don’t have the conviction or the necessary pattern matching to evaluate them sufficiently.

We can think of this in terms of the secretary problem. The secretary problem is a fairly old puzzle (that was asked to me when I was interviewing for a quant job at Goldman Sachs in 2009).

You need to hire the best possible secretary out of a 100 possible candidates. You need to make the decision “online” - if you reject one candidate, you cannot go back to him.

What is the strategy you need to follow to maximise your chances of hiring the best possible secretary, assuming they come in random order?

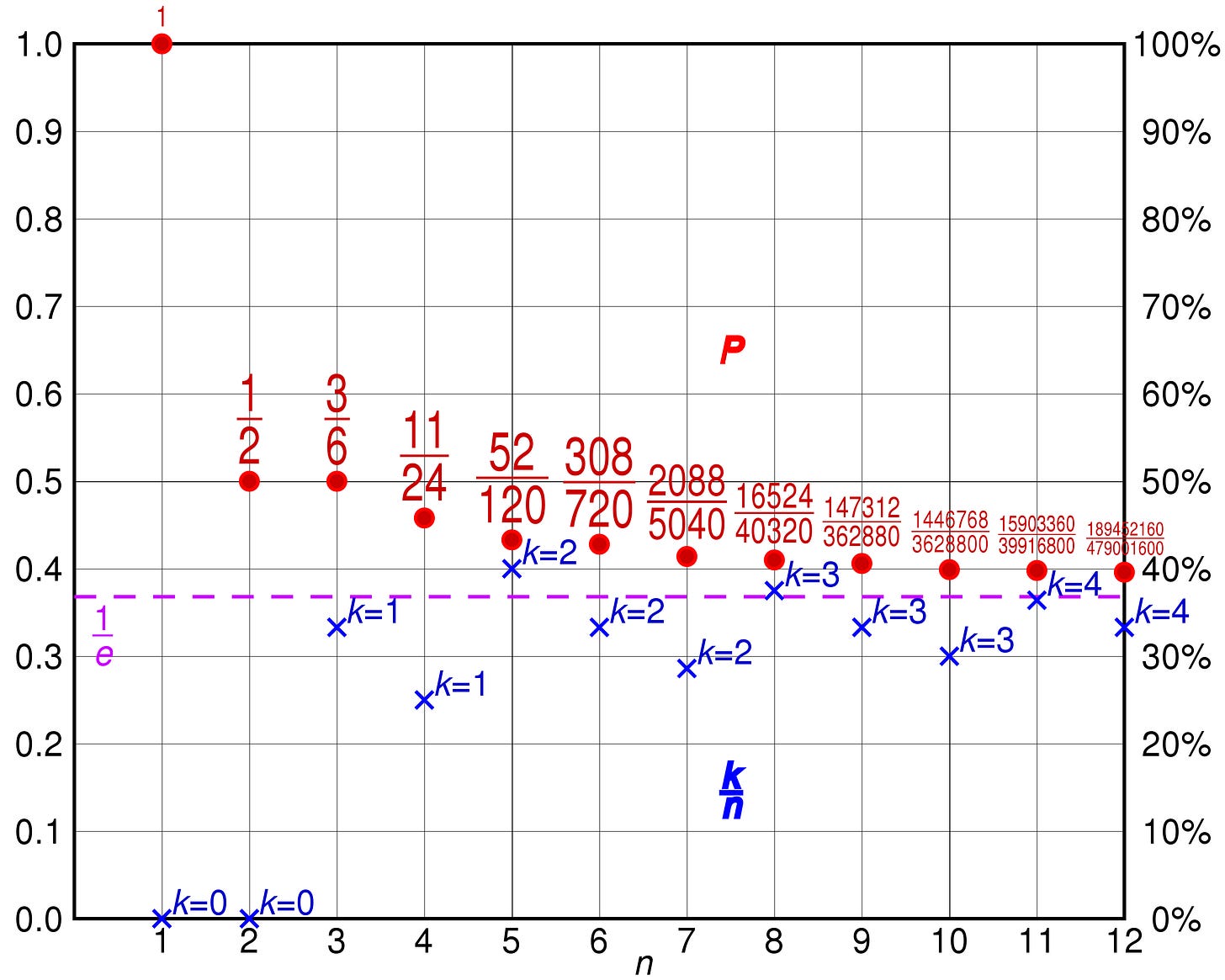

The optimal solution (which I won’t go into here - but possibly went into when I got my job at Goldman) is that you don’t hire any of the first 37 (or a proportion of

of the overall number of candidates), but instead evaluate them and find the best level among them. This is the benchmark. After this, you simply hire the first secretary who beats this benchmark.

Earlier this evening I was at the annual meetup of the Bangalore chapter of the IIT Madras Alumni Association. I was talking to Praneeth (I promised him I’ll credit him for this thought, hence linking to his LinkedIn) about Babbage, and he was asking about our fund raising process. And that’s when I realised that the secretary problem explains why some possibly unique (for their time) startups don’t get funded - they are part of the 37%.

Companies that stand out too much may not get funded because they are part of the 37%, or the “training set”

Basically, if a company that you see doesn’t fit any of your pretrained models, there are three things you can do with it. One is to “put NED” and not bother about the company - the effort required to evaluate it is too high. The second is to enthusiastically evaluate, and take a punt for some reason (maybe you really like the founders, or have sufficient sponges that you can waste one sponge by making a risky bet). The third, and possibly most likely, is that you will use this as a data point to make a new pretrained model.

And until the VC has enough data points to train this new pretrained model, every company they meet that fits this template will be just that - a data point as part of the pretraining process. The optimal solution to the secretary problem mandates that none of the first 37% be hired - they are purely there to set the benchmark and train the model.

So, if an idea is ahead of its time, it is likely that it is part of every VC’s 37%. And thus it won’t get funded, but helps the VC make a thesis on the broad area. A later similar idea can then piggyback on this and get evaluated by the VC’s pretrained model and get funded!

The secretary problem is more far-reaching than we think!