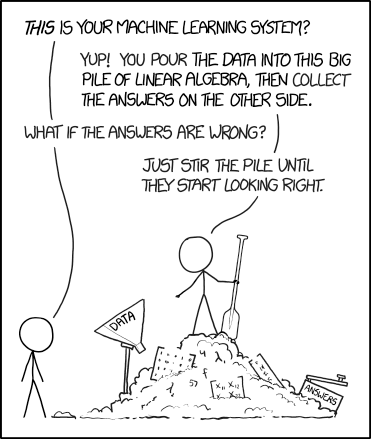

Chess, Bridge, AI Coding and Data Science

LLMs are not yet good at data science because data science involves a LOT of opinion, and that means the "average opinion" that the LLM espouses my not tally with the data scientist's opinion

I started playing chess competitively in 1994. For a year or two after that I remember going to several city and state level tournaments, both age group and otherwise. By the end of 1995 (or early 96), I was done. I had completely stopped enjoying myself.

Around 2001/2 I learnt to play contract bridge. I was hooked very soon. It took me a while to get good at it, but it was very clear to me that I was not going to get bored with this. Perhaps the only reason I didn’t play more of it was because of the difficulty of finding three other players (including a steady partner) to play with. So after graduating from IIT Madras, I gave it up.

I know that if I were to join a bridge club now (and have time for it), I’ll get hooked once again and play regularly. I can’t say the same thing about chess.

Both are mind games but what sets them apart is the complexity and randomness - chess has the same starting position in each game (I’m not talking about Fischer Chess / Chess 960 here - that’s a different sport). Most games start from one of a few tens of openings. You need to know long theoretical lines. And you get a handful of classes of positions at the end of it.

Yes, chess is not “solved” yet (unlike checkers), but the lack of randomness means that computers are rather good at it. More importantly, from my perspective, it can get a bit boring.

Bridge, being a card game, is rather different. Each game starts with a different lie of cards, and that makes it rather interesting. Of course, it is also made more complex because it’s an imperfect information game - apart from yourself and the dummy, you don’t know which cards lie where. And that keeps it fun. And keeps the complexity.

Enough about sports now. Let’s talk about AI and coding.

As the more perceptive of you might have realised by now, AI has gotten significantly better at coding over the last couple of years. Gone are the days when you would ask for a piece of code, and it would give you something that only worked in an outdated version of Python. Nowadays, it is possible to write fairly complex code without actually writing a single line of code (eg. take this voice notes app I’ve built, and not used much!).

What makes AI rather good at the code is that it is verifiable. It is relatively easy to automate testing for code, assuming you have a reasonably “intelligent” agent doing so. So the AI first figures out what code needs to be written, then writes the code, then writes test beds to verify the code (I’m oversimplifying), then runs these test beds to make sure that the code does what it is supposed to do, and iterates.

Given that LLMs now have planning modes and fairly long contexts, it is now very possible for them to run multiple iterations to get the code right and then “ship” it. You and I are now able to write fairly complex pieces of software without actually coding. The usual doomer suspects are shouting wolf yet again.

In a way, software engineering is like chess. It is a complete information game. Apart from various inputs that a user can give (which can be put into a finite number of classes), the whole thing is fairly deterministic and well-known. This makes it easy to verify and get right over a period of time.

In that sense, software engineering is like chess. Data science, on the other hand, is like bridge (maybe I retain interest in it despite having worked in it for nearly two decades; this is very much unlike software engineering where my interest broadly lasted from 1998 to 2002).

Think of a reasonably straightforward data science task. There is some data that you need to inspect and clean, and use it to build a machine learning model to predict something. As vanilla as it gets in the data science world.

How would an intelligent data scientist (this doesn’t include all data scientists) approach it? One step at a time.

First figure out the right set of data to download (and understand the database structure, quirks of the data, etc. in the process). Do a bunch of data explorations. Take some averages and distributions. Plot some graphs. Based on all these outputs, generate some intuitions about the data.

Figure out if any transformations are required (this is a function of the prior analyses, and what one has observed in them), and then experiment to figure out what transformations make sense.

And in the process, also clean the data - figure out what data is spurious and needs to be thrown away. Figure out what needs to be done when data goes missing. Figure out how to deal with cases where there are some obvious errors in the data (one value being entered in grams while the rest of the column is in kilograms, for example). Use your judgment to do all of this.

Then you have a clean dataset which you dutifully split into train and test (this is the most mechanical part of the data science process, which a lot of data scientists strangely give a lot of weight to. It is the classic “necessary but not sufficient” thing!).

Anyway, now you build out a ML model and check for accuracy. Inspect the output to see if there are any particular biases, which can lead to further data transformations. Maybe experiment with a bunch of ML techniques before you (once again) settle on XGBoost.

The whole thing, as you realise, is an iterative process. For each step, you rely on the outputs of all the previous steps. I guess this is why you have things like interactive Jupyter notebooks - a concept that is otherwise alien to software engineering (where most languages are compiled, and not interpreted, any way!). And in each step, you need to use judgment, which includes business context, prior knowledge and several other things.

And this is why LLMs have not yet become good at data science. Like the name of this newsletter suggests, data science is actually an art. There is a lot of judgments one needs to make in the iterative process. Most of these judgments involve the data scientist’s opinion (and not just hard technical skills).

Can an LLM do this? Absolutely. Just build an agent that does the process step by step, where the output of each step is fed as context into the next step (curious - do any data science based IDEs / coding agents already do this?). Have a whole bunch of the company’s information and the data science team’s “priors” and past analyses and judgments in one very large context file. In theory, based on all this, the LLM should be able to produce a machine learning model.

However, is this the model that the data scientist wants? The number of places where the LLM puts in its opinion (in terms of determining the next step) is large enough that there could be a marked difference between what the data scientist wants and what the LLM does.

And after all this, what defines a “good model” is subjective. Some data scientists like to simplify this by just going R^2 (or ROC-AUC) hunting. However, in most cases this doesn’t necessarily represent the best model. One needs to inspect the confusion matrix. One needs to figure out the costs of errors (of omission and commission) in this particular case and draw the boundaries appropriately. Some errors are more acceptable than others, and that determines what model is chosen.

All in all, there is way too much judgment in the data science process, and thus way too many degrees of freedom for the LLM to express its opinion. Most LLMs simply go the “average” route, with the most likely opinion in each case. However, this may not tally with the opinion of the data scientist (and most good data scientists are rather opinionated).

In other words, data science is like bridge. That is what keeps it interesting (for people like me). That is what makes it harder for computers to “crack”. There is also the imperfect information thingy - sometimes business itself doesn’t know what it wants from a piece of analysis, and so the data scientist is working under that uncertainty!